When my husband and I were transitioning out of full-time camper life last summer, we made a list of things we wanted to do when we plopped down somewhere. On this list were travel goals like doing more intentional trips, creative goals like taking craft classes, and domestic goals like growing an edible garden. There’s are many things you can do while living nomadically on the road, yet lots of other things that work out better when you have a consistent home base.

A couple other goals on this list were doing some local volunteering and making new friends wherever we ended up. Over the past couple months, I started browsing meetup groups and event pages to see how we could break out of our little bubble and start building a bit of community here in New Mexico. An Albuquerque REI events page listing led me to discover a group called New Mexico Volunteers for the Outdoors, which is “an all-volunteer, non-political organization that is dedicated to improving trails and outdoor facilities throughout the state.”

This sounded pretty rad, so I signed us up for a trail-building project at Embudo Canyon, which is part of Albuquerque’s Open Space trail network. One of my favorite parts about the Albuquerque area (and New Mexico in general) is its wide-open spaces, so this seemed like a great way to spend a Saturday morning.

We arrived at the trailhead parking lot just before 8am and found a couple tables set up for volunteers. One table was packed with coffee, juice, and breakfast foods, while the other one had sign-up sheets and waiver forms. Compared to other outdoor volunteering projects I’ve joined in the past, this group really had its act together and was impressively well-organized.

There were about 20-25 volunteers who showed up this particular morning to build a new trail through the foothills terrain and close off an old trail that had become really eroded. Volunteer leaders from NMVFO and a few guys who worked for the Open Space Division briefed us on the different tools to use and where to collectively focus our efforts on various portions of the trail.

Before committing to this trail work project, I tipped the volunteer coordinators off on the fact that I was 33 weeks pregnant and might be taking it a bit easier than some of the other people who showed up. They reassured me that this was a chill environment and that there would be plenty of different assignments to do with varying degrees of intensity. I felt great working out there with a tiny human in my belly and largely attribute my easy and positive pregnancy so far to my staying active and getting reasonable exercise every day. Fortunately, there was also a port-a-potty at the trailhead for those frequent pee breaks that pregnant women around the world know all too well.

During the course of the morning, we used pick axes, McLeod tools, and shovels to remove brush, rocks, and cholla and prickly pear cacti from the new trail. Then we worked to level out and stamp down the terrain with a good slope to make it more hikeable. The most challenging part to me was figuring out the best slope/grade/angle for the new trail. Rather than stress about or waste time, I mostly just dug up stuff and left the planning work to the leaders who had done this countless times before. Other volunteers did “rock work,” collecting and carrying rocks to bank steep edges of new trail, and later transplanted removed debris to the old trail to block it off and discourage hikers from using it.

The group leaders and other volunteers were really friendly, welcoming, and just seemed like genuinely good people. They were patient while showing us the best ways to go about trail building and appreciative of even the smallest contributions during the day. Group shot!

By the end of the day, our group built 700 feet of new trail and closed off 600 feet of old trail in this beautiful open space. One of the volunteers, Kevin, made this great video that shows what trail work is all about. My interview even made the final cut – scroll to 1:09 to hear me blabbing about why I signed up for the project.

As the self-quarantine lifestyle has become our new normal, NMVFO’s upcoming volunteer meetups have been cancelled, along with pretty much everything else across the country right now. It’s necessary to keep people safe, but I’m just glad we were able to participate in one of these events before going on a more serious lockdown.

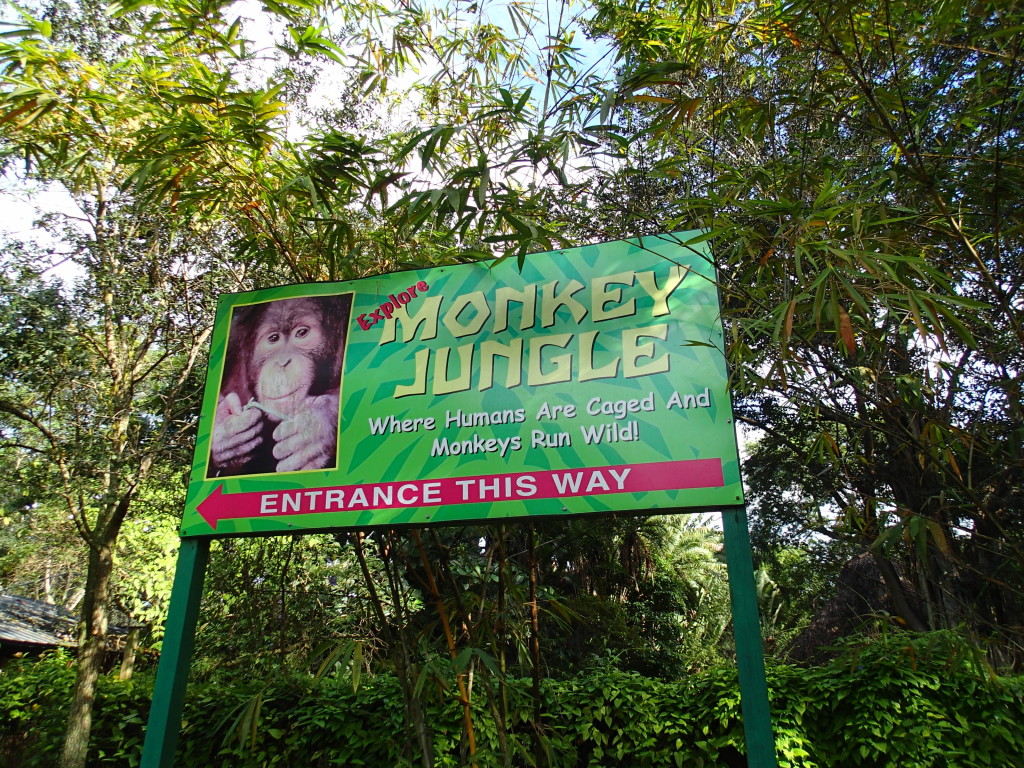

Although we can’t join any other meetup events for the foreseeable future, we’re already taking what we learned in Embudo Canyon and applying it to our own property. To make the most of our 2+ acres, we started building our very own trail around our house last weekend. There’s obviously a lot more work that needs to be done here, but once it’s complete, I think this will be an awesome place to take Monkey and Baby Boy out for walks – perhaps even being where the little guy goes on his very first hikes to explore the beauty of the New Mexico wilderness.

There are no safer places to be right now than in the outdoors at home, so while we wait for the next volunteer opportunity to get involved with, this little trail in our yard gives us a fun project to focus on while staying active and giving us an extra boost of hope for the days ahead.